Related You Tube video: https://youtu.be/WNw71tfpK0c

One of the underlying motives to define best practices within an organization is to reduce the mistakes made by staff and managers. The resulting document can be used to train and remind people on expected practices.

When an organization commits to define best practices, it must decide how much detail to include in the guidelines and templates. One common tendency is to either write several tomes, hoping that each tome will be read and used, or make the document so abstract that it does not contain any guidance.

In this article I will describe the use of checklists as a way to concisely document practices and find mistakes in an organization’s work.

Background

In 2009, Atul Gawande, associate professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School, wrote a book titled, Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right[1]. The book details many stories on the development and use of checklists in healthcare, aviation, and other industries.

The basic premise of the book is that a simple checklist can ensure that critical steps have not been overlooked, either due to haste, forgetfulness or inexperience. In the book, measurements were collected from surgeries performed around the world before and after the checklist was employed. The results were:

- Major complications down by 36%

- Infections down by approximately 50%

- The number of patients returned to surgery because of problems declined by 25%

- 150 fewer patients than normal suffered harm from surgery (measured over 4,000 patients)

- 27 fewer deaths (47% drop) caused from surgical complications

The surgery checklist was used at three pause points in a surgical procedure: before induction of anesthesia, before skin incision, and before the patient left the operating room. The checklist was described on one page, took one or two minutes to conduct, and contained 22 steps organized into 3 groups. See the link below.

Guidelines for creating checklists

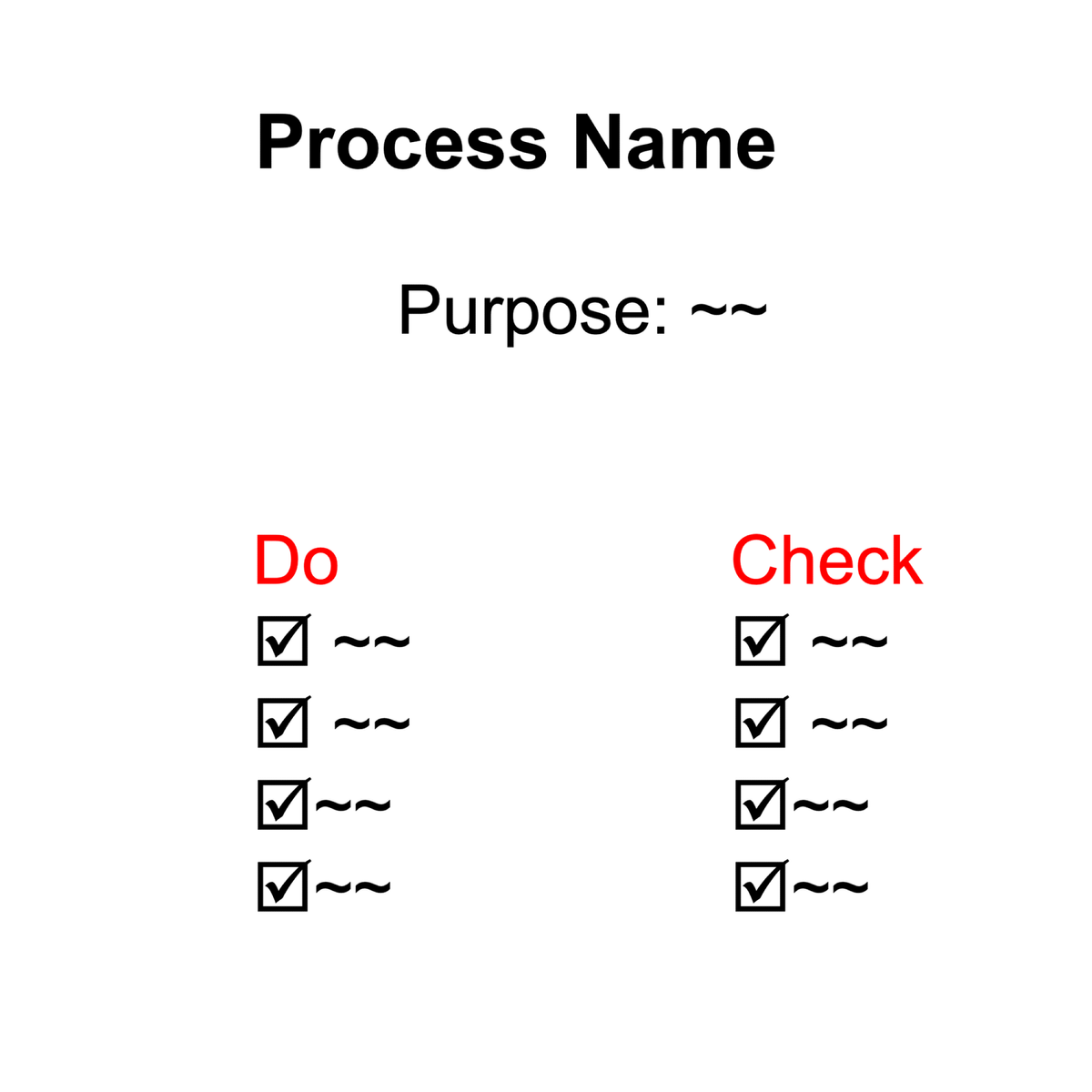

- Select from two main styles of checklists: “Do-Confirm,” where critical steps (that should have already been performed) are verified; and “Read-Do” checklists that state what steps to perform given specific situations.

- Select pause points in your team’s work flow where the completion of critical steps can be verified.

- Condense the checklist onto one page and use single bullet point sentences.

- Ensure items on the checklist are critical (high-risk) and are not already covered by other mechanisms.

- Label the checklist with a title that reflects its objective, such as “Before project start checklist,” “After requirements gathered checklist,” or “Handoff of product to final shipment checklist.”

- Run the checklist verbally with the team to ensure that anyone that has an issue can speak up. Assign someone to read the checklist out aloud who can remain objective and undistracted.

- Plan to revise the checklist content and implementation numerous times until it is able to quickly detect serious problems.

How you could use checklists

- Select the areas in your project or organization where you have pain points and turn existing ignored process documents and guidelines into checklists that your team can use.

- Follow the guidelines below for creating checklists. See the link below.

- Put any excessive information not needed on the checklist into training material; reserve the checklist for high-risk and critical steps.

Next Step

If you would like assistance in implementing these ideas, please use the contact us form.

References

1 Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right, Metropolitan Books, 2009.